Black Suffrage Leaders Fought for More Than the Right to Vote

African-American suffragists were not only exceptional women demanding the right to vote—they also continued the struggle for racial equality. As activists for the 19th Amendment, they were told to observe racial segregation during suffrage marches, and their considerable contributions were often minimized.¹

Still, regardless of the opposition they faced, these strong women stood tall and became key figures in civil liberties and justice movements. They were former slaves, writers, poets, journalists, teachers, and doctors. Pushed out of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) because of their race, they formed the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 with Mary Church Terrell at the helm, and heroines such as Harriet Tubman, Frances E. W. Harper, and Ida B. Wells as founding members.²–⁴

Even after the passage of the 19th Amendment, the struggle for Black civil rights was far from over. Segregation and Jim Crow laws suppressed the Black vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965. However, in 2013, the Supreme Court significantly weakened the VRA in Shelby County v. Holder by eliminating protections against discriminatory voting changes.⁵ These changes led to an onslaught of voter suppression tactics, including discriminatory voter ID laws, registration restrictions, voter purges, felony disenfranchisement, and gerrymandering of voting districts.⁶

Tennessee Black Suffrage Leaders

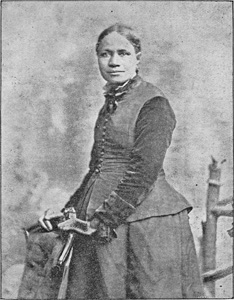

Mary Church Terrell From Memphis, Tennessee

Mary Church Terrell From Memphis, Tennessee

Mary’s parents were former slaves, but her father became the first African-American millionaire in the South through real estate investments, while her mother was the first African-American woman to own and manage a hair salon. Mary earned a master’s degree in Education from Oberlin College in 1888 and became a teacher, writer, and journalist.

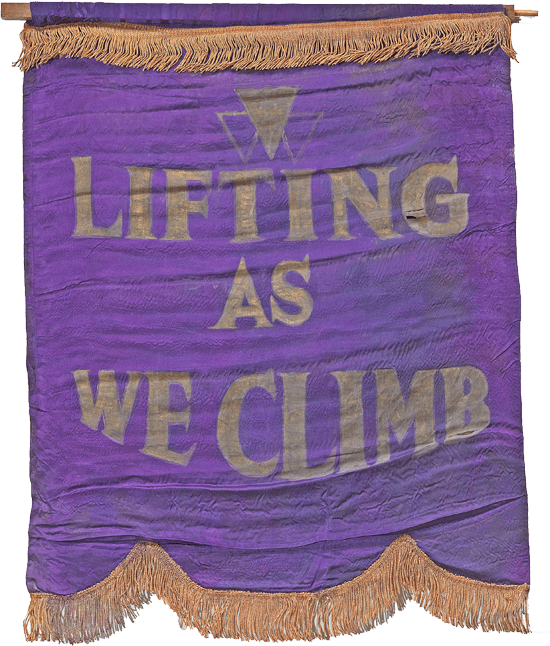

After the lynching of her friend Thomas Moss in 1892, Mary began to campaign with Ida B. Wells for racial equality and women’s suffrage. Her motto, “Lifting as we climb,” became the guiding principle of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which she helped found. She was also a founding member of the NAACP, the Colored Women’s League of Washington, the first president of the NACW, later co-founded the National Association of University Women, and became president of the Women’s Republican League. Even in old age, she protested and successfully sued against segregation at restaurants in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Mattie E. Coleman From Sumner County, Tennessee

Dr. Mattie E. Coleman From Sumner County, Tennessee

Mattie was the daughter of an African Methodist Episcopal minister and graduated from Meharry Medical College in 1906 as one of Tennessee’s first African-American female physicians.

As a feminist and social activist, she founded the Woman’s Connectional Missionary Council and worked closely with white Methodist women to build community services through the Bethlehem House settlement. Mattie is believed to have initiated the biracial alliance that formed in Nashville and became critical to the women’s suffrage movement.

Mattie was appointed “State Negro Organizer,” alongside Juno Frankie Pierce as “Secretary of Colored Suffrage Work,” by the Tennessee League of Women Voters. Together, they registered a remarkable 2,500 African-American female voters in Nashville in 1919.

Juno Frankie Pierce From Nashville, Tennessee

Juno Frankie Pierce From Nashville, Tennessee

Born to a house slave and a freedman, Juno grew up to be a teacher and suffragist. She became president of the Negro Women’s Reconstruction League, founded the Nashville Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and was a member of the first Committee of Management of the Blue Triangle League of the YWCA.

She was later invited to address the first meeting of the newly established League of Women Voters of Tennessee. In working closely with the League, she asked white women for the same recognition they had sought from men:

“We are asking only one thing—a square deal. We want recognition in all forms of this government. We want a state vocational school, a child welfare department of the state, and more room in state schools.”

Together with Dr. Mattie Coleman, she advocated for the establishment of the Tennessee Vocational School for Colored Girls, which became part of the legislative agenda of the Tennessee League of Women Voters. Juno became the first superintendent of that school, serving for eighteen years. She was succeeded by Dr. Coleman.

In 2019, Nashville opened Frankie Pierce Park to honor her achievements.

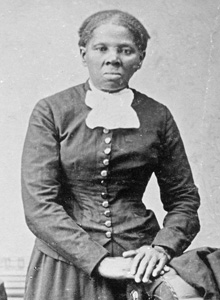

Ida B. Wells-Barnett From Holly Springs, Mississippi

Ida B. Wells-Barnett From Holly Springs, Mississippi

Born into slavery during the Civil War, Ida lost her parents and a sibling to yellow fever at age 16 and became a teacher to care for her younger siblings.

After moving to Memphis, she sued a train company for forcibly removing her from a first-class car despite her ticket. She began investigating lynchings after the murder of a friend. As an investigative journalist and newspaper owner, she published extensive research, including Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases and The Red Record, outlining the economic and social motivations behind lynchings.

Her life was endangered for speaking out, and her newspaper office was destroyed, forcing her to leave the South. After marrying a lawyer, she continued her anti-lynching work and suffrage activism.

Ida co-founded the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, which helped elect the city’s first Black alderman.

Frances E. W. Harper From Baltimore, Maryland

Frances E. W. Harper From Baltimore, Maryland

Frances was born free, but orphaned at age three and raised by her uncle and aunt. She became a writer, poet, teacher, abolitionist, suffragist, and speaker, using her earnings to support the Underground Railroad.

Over 100 years before Rosa Parks, she refused to ride in the “colored section” of a Philadelphia trolley. After the Civil War, Frances taught newly freed people in the South, co-founded the American Woman Suffrage Association, and helped freedmen in Alabama acquire land during Reconstruction. In 1892, she published Iola Leroy, one of the first novels by an African-American woman, addressing race, gender, and citizenship. She worked with Mary Church Terrell in the NACW and became vice president in 1897.

In her poem Bury Me in a Free Land, she writes:

“I ask no monument, proud and high to arrest the gaze of the passers-by;

All that my yearning spirit craves is, bury me not in a land of slaves.”

She died in 1911 at age 86 and was buried in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.

Harriet Tubman From Dorchester County, Maryland

Harriet Tubman From Dorchester County, Maryland

Born into slavery, Harriet suffered a traumatic brain injury at a young age after being struck by an iron weight, leading to lifelong health issues and vivid dreams she believed were divine visions. At 27, she escaped slavery, traveling alone at night along the Underground Railroad.

Returning to Maryland multiple times, often with a revolver for protection, she rescued over 70 people and guided many others. She earned the nickname “Moses.”

During the Civil War, Harriet served as a Union Army scout and became the first woman to lead an armed assault. She guided steamboats during the Combahee River Raid, rescuing around 750 enslaved people.

Later in life Harriet was a strong supporter of the women’s suffrage movement working alongside Susan B. Anthony and Emily Howland. She traveled around the country speaking of her actions during the Civil War and the sacrifices of other women throughout history to rally support for women’s suffrage.

In her late 70s Harriet underwent brain surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital – without anesthesia. She chose to bite down on a bullet instead, which is what she knew from the Civil War, when a soldier’s limbs were amputated.

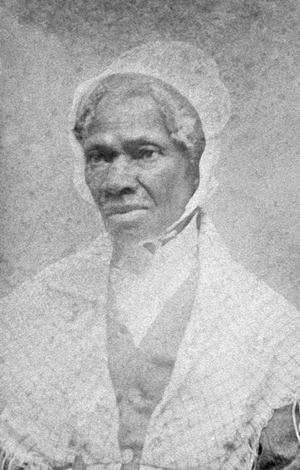

Sojourner Truth From Rifton, New York

Sojourner Truth From Rifton, New York

Born into slavery in New York as Isabella Baumfree, Sojourner Truth freed herself in 1826 and later changed her name to reflect her life’s purpose: to travel and spread truth. A deeply spiritual woman, she became a fierce and fearless voice for abolition and women’s rights at a time when both movements often excluded Black women.

Truth is best known for her powerful extemporaneous speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” delivered in 1851 at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. In it, she challenged both racial and gender inequality, boldly asserting Black women’s rightful place in the suffrage movement. Unlike many white suffragists of her time, Truth linked the struggles of enslaved people with the oppression of women, making her one of the earliest and most enduring voices for intersectional justice.

Though she could not read or write, Truth’s speeches were widely published and her advocacy left an indelible mark on the American conscience. She met with President Abraham Lincoln, recruited Black soldiers during the Civil War, and later fought for land rights for freed people.

Sojourner Truth’s legacy continues to inspire generations fighting for racial and gender justice.

The Nashville Alliance

In 1919, during an era when racial violence—including brutal assaults and lynchings—was tragically common throughout the South, an uncommon alliance formed in Nashville. Women of color and white women came together around the shared cause of women’s suffrage and in support of social services for African American communities. This biracial coalition was extraordinary, especially in the South, where many white suffragists actively excluded Black women from the movement, advocating for their own right to vote while denying that same right to others.

Nashville was home to a strong African American middle class, bolstered by institutions like Fisk University, Walden University, and Meharry Medical College. Leaders such as Dr. Mattie Coleman and Juno Frankie Pierce were at the forefront of organizing Black women’s clubs, laying the groundwork for interracial collaboration in the city. These women partnered with white women from the Methodist Episcopal Church South—one of the few spaces at the time where Black and white women worked side by side. Dr. Coleman even attended the white Methodist Women’s Council in 1918 and was invited to participate in white suffrage meetings—an extraordinary gesture for that time.

Catherine Talty Kenny, chair of the League of Women Voters of Tennessee (LWVTN), formed a close alliance with both Dr. Coleman and Mrs. Pierce. Unlike many Southern suffrage leaders, Kenny believed in the power and importance of the Black female vote. She helped ensure Black women had a place at the table during the League’s founding. Notably, Pierce delivered the keynote address at the League’s inaugural meeting. Their collective efforts helped register more than 6,000 women to vote in Nashville in 1919—including over 1,300 Black women.

Resources

- For an extended list of high-profile suffragists of color, please visit the Turning Point’s Suffragist Memorial website.

- Download the full feature issue of The Crisis in support of Votes for Women published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in August 1915 in New York. Please also note that at the time of publishing in 1915, the swastika (used here to divide sections of the article) was a common printer’s stock symbol with no connection to anti-Semitism.

References

- National Park Service, Between Two Worlds: Black Women and the Fight for Voting Rights, Series: Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments, Jan 14 2020. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/articles/black-women-and-the-fight-for-voting-rights.htm

- Buechler, Steven M. (1990). Women’s Movement in United States: Woman Suffrage, Equal Rights and Beyond. Rutgers University Press.

- Mezey, Susan Gluck (1997). “The Evolution of American Feminism”. The Review of Politics. 59 (4): 948–949. doi:10.1017/s0034670500028461. JSTOR 1408321.

- Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn (2004). “Discontented black feminists: prelude and postscript to the passage of the nineteenth amendment”. In Bobo, J. (ed.). The Black Studies Reader. New York: Routledge. pp. 65–78.

- Brennan Center for Justice (2018). “How We Can Restore the Voting Rights Act”. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/how-we-can-restore-voting-rights-act

- Rafei, Leila. American Civil Liberties Union (February 3, 2020). “Block the Vote: Voter Supression 2020”. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/news/civil-liberties/block-the-vote-voter-suppression-in-2020/

- League of Women Voters (December 4, 2019). “League Urges Congress to Vote Yes for H.R. 4, Voting Rights Advancement Act”. Retrieved from https://www.lwv.org/fighting-voter-suppression/league-urges-congress-vote-yes-hr-4-voting-rights-advancement-act

- History of Woman Suffrage. Rochester, Anthony. 1887–1902. p. 116. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/historyofwomansu01stanuoft/page/n12/mode/2up

- Goodstein, Anita Shafer. “A Rare Alliance: African American and White Women in the Tennessee Elections of 1919 and 1920.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 64, no. 2, 1998, pp. 219–246. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2587945. Accessed 5 Mar. 2020.

- Oertel K.T. “Harriet Tubman (Routledge Historical Americans)” Routledge 2015. ISBN 978-0415825122

- Clinton, C. “Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom” Back Bay Books 2005. ISBN 978-0316155946

- Larson, K.C. “Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero” One World 2004. ISBN 978-0345456281

- Norwood, A. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett.” National Women’s History Museum. 2017. Retrieved from www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-wells-barnett.

- Wells-Barnett, I. B. “Southern Horrors – Lynch Law in All Its Phases” Project Gutenberg. 2007. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htm

- Schechter, Patricia (2001). Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Yee, S. (2007, February 11) Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911). Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/harper-frances-ellen-watkins-1825-1911/

- “Extracts from a letter of Frances Ellen Watkins” (PDF). The Liberator. April 23, 1858. Retrieved from http://fair-use.org/the-liberator/1858/04/23/the-liberator-28-17.pdf

- Hubbard, LaRese C. (2008-03-31). “When and Where I Enter”. Journal of Black Studies. 40 (2): 283–295. doi:10.1177/0021934707311939. ISSN 0021-9347

- Harper, F.E.W. Project Gutenberg (2004). „Iola Leroy“ Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12352/pg12352-images.html

- Yellin, C.L.; Sherman, J. (2016). The Perfect 36 : Tennessee Delivers Woman Suffrage (Second ed.). Memphis, Tennessee: Vote 70 Press. ISBN 9780974245652. OCLC 1002855678

- Bucy, C.S. (2017). Juno Frankie Pierce. Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved from https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/juno-frankie-pierce/

- Goodstein, A. (1998). A Rare Alliance: African American and White Women in the Tennessee Elections of 1919 and 1920. The Journal of Southern History, 64(2), 219-246. doi:10.2307/2587945

- Smith, J.C. (1992). Notable Black American Women. VNR AG. pp. 125–128. ISBN 9780810391772.

- Aaseng, N. (2014). African-American Religious Leaders: A-Z of African Americans. Infobase Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 9781438107813.

- Goodstein, A. (1998). A Rare Alliance: African American and White Women in the Tennessee Elections of 1919 and 1920. The Journal of Southern History, 64(2), 219-246. doi:10.2307/2587945

- Michals, D. “Mary Church Terrell.” National Women’s History Museum. National Women’s History Museum, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-church-terrell

- Smith, J.C.,ed., “Robert Reed Church Sr.”, in Notable Black American Men, 1 (Detroit: Gale Research, 1999), 202.

- McCluskey, A.T. “Setting the Standard: Mary Church Terrell’s Last Campaign for Social Justice.” Black Scholar, vol. 29, no. 2/3, Summer 1999, p. 47. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/00064246.1999